Hurricane Sandy devastated much of the Mid-Atlantic Coast

this week with ferocious winds, record-setting storm surge and destructive

waves. While the economic toll from this disaster could total up to $50 billion

(Huffington Post, November 2, 2012), the staggering human loss has made this

storm a catastrophe. The latest death toll has risen to 80 fatalities in the

U.S., including 38 victims in New York City (New York Times, November 2, 2012.)

The record-breaking storm surge, which smashed ashore most

viciously in New Jersey and New York, caused many of these fatalities and much

of the damage. On Staten Island, for example, a two-year-old boy drowned when

the surge swept him from his mother’s arms (New York Times, November 1, 2012).

Photos of the surge damage depict homes which were either smashed to pieces or

floated off their foundations, as well as debris-covered streets, which were

also buried under feet of sand.

Preliminary surge observations have provided a maximum surge

level of 14.6 feet at Bergen Point, NJ (www.abcnews.go.com.)

However, surge levels were devastatingly high all along the New Jersey Coast,

in the metropolitan New York City area, on Long Island, and even in coastal New

England.

Battery Park, NY, located at the southern tip of Manhattan

Island, set a new record high water level of 17.33 feet above the station

datum, a vertical reference line for measuring water heights. This water level

was reached through a combination of high astronomical tides and a 9.23-foot

storm surge, which is the storm-driven water height above normal tide levels.

Such high water levels enabled salt water to pour over sea walls in Lower

Manhattan and inundate the subway system under many feet of water.

Sandy’s water level at Battery Park broke Hurricane Donna’s

(1960) previous high-water record by more than four feet. It is also

interesting to note that Hurricane Sandy’s massive surge comes just 14 months

after Hurricane Irene inundated much of the coastline, producing the fourth

highest water level of all time at Battery Park.

These surge observations will be incorporated into SURGEDAT,

the world’s most comprehensive storm surge archive. This dataset has been

developed through funding made possible by NOAA-funded SCIPP, the Southern

Climate Impact Planning Program. SURGEDAT has identified the peak storm surge

level in more than 450 global surge events since 1880, including more than 300

events in the United States. Recently this dataset was expanded to include the

entire inundation footprint for more than 240 U.S. surge events. These

footprints contain more than 6,100 historic storm surge observations in the

United States.

These data are useful for coastal decision makers, emergency

management professionals, insurance professionals, as well as coastal

scientists and storm surge modelers. For example, such data are very useful for

risk-assessment studies, which identify critical inundation thresholds, such as

the 100-year storm surge level for a given location. These data are also useful

to validate storm surge models, which often need actual observed data to

validate model runs.

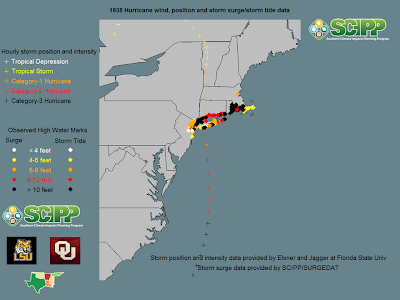

Prior to Sandy’s landfall, SCIPP mapped out hurricane paths

and inundation envelopes for five previous hurricanes that generated storm

surges in the New York City area. These maps provided historical context as

Sandy approached. One of the key messages of these historical maps is that

Sandy’s storm track was unprecedented along the Mid-Atlantic Coast. These maps

also provided evidence that the area of coastline near New York City is very

effective at funneling in storm surge, presumably because water gets trapped in

this area. Storm surge levels during the 1944 Hurricane and Hurricane Donna

(1960) were higher in this region than other areas along the coast- a

realization that hopefully encouraged many people in the metro New York area to

evacuate Sandy’s devastating storm surge.