Sandy to Generate Unprecedented Storm Surge in Northeast

Hurricane Sandy will generate an unprecedented storm surge

along the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast Coast on Monday and Tuesday. In this blog

post, I will answer questions I’ve been receiving about this surge event.

1.

Will

Sandy’s surge really be worse than previous storms?

Sandy will likely produce a large and destructive storm

surge along the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast Coast. Sandy’s track, or storm path,

is unprecedented, so it’s a bit difficult to compare this storm with other

surge events. Unfortunately, Sandy will approach the coast from the southeast

and make landfall south of New York City. This is likely the

worst-case-scenario track for New York. Surge tends to pile up to the right of

the storm track, and this storm will very effectively pile up water in New

Jersey, New York, and Southern New England.

2.

Is it

a good sign that Sandy is forecast to “miss” New York and make landfall in New

Jersey?

Sandy’s forecast landfall along the central New Jersey Coast

is actually a worst-case storm track for the New York City area, at least in

regards to storm surge generation. THIS

STORM TRACK HAS NEVER BEEN OBSERVED IN MODERN HISTORY, so there is a lot of

uncertainty as to what it means. It is very possible that a catastrophic surge will

devastate the coast, especially in Northern New Jersey, New York City and Long

Island, with a peak surge that could exceed 12 feet in some areas.

Keep in mind that a large hurricane like Sandy will generate

very widespread and severe impacts, so it will be hard to “miss” this storm,

even if the track shifts. Catastrophic storm surge may extend from the Delmarva

Peninsula to Cape Cod. The exact track will not matter so much for many people,

unless you manage to get on the “left” side of the storm track, where surge

levels will be much lower.

3.

When

should I evacuate?

Sandy has a very large wind field. This enables the storm to

push a lot of water, even long before the storm approaches landfall.

Hurricane Ike was a large hurricane that hit Texas in 2008.

Although the storm was only a category-2 on the Saffir-Simpson scale, its

massive size enabled it to push tremendous amounts of water, flooding

evacuation routes as long as 24 hours before landfall. More than 600 people had

to be evacuated from the Bolivar Peninsula because they waited too long, and

their evacuation routes were flooded by the time they decided to leave.

If you’re in coastal New Jersey, low-lying areas of New

York, coastal Long Island or Long Island sound you may need to evacuate ASAP to

avoid drowning in this event! This may be a life and death scenario for many people

in coastal communities!

4.

How

does Sandy’s surge height and extent compare to other hurricanes?

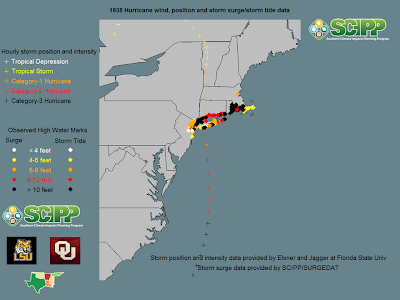

The Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP) at

Louisiana State University and the University of Oklahoma has created the

world’s most comprehensive storm surge database, which has now identified more

than 6,000 high water marks along the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. We’ve

identified surge and storm tide levels for several major storms that impacted

the New York City area. See previous blog posts for the storm track and water

levels of these storms.

The major difference with Sandy is that it is taking an

unprecedented track. Instead of moving northward, along the coast, the storm is

forecast to take a turn to the west and make landfall in a more perpendicular

fashion (coming at the coast instead of riding along the coast.) This should

much more effectively pile up water in Northern Jersey, near New York City,

along Long Island and Long Island Sound.

5.

What

exactly is storm surge? Does that water level include waves?

A storm surge is really a dome of sea-water that is

elevated. This dome may extend for hundreds of miles. The storm surge level is

the height to which the sea level is raised above normal, and this height does

not include waves. Think of it as a new sea level.

So if a community with an elevation of five feet above sea

level is inundated with a 12-foot surge, this means the water will be about

seven feet above street level. This water level does not include large,

destructive waves that will pound buildings near the coast.

6.

What

do you mean when you say water will be “pushed into the corner” near New York

City?

The shape of the coastline can greatly increase the storm

surge levels. Concave areas of coastline, which bend “inward,” generally trap

storm surge and create higher water levels. The coastline near NYC curves on a

sharp angle, which will greatly elevate surge levels, especially if a storm

makes landfall south of NYC. However, storms usually approach NYC from the south,

and curve to the east before approaching the city, making this piling up

process less effective.

For our friends in the Northeast who are more accustomed to

shoveling snow than dealing with hurricanes, think of this example. Do you know

how snow can pile up in a corner when you have to shovel your driveway? As you

push snow along and you approach a corner, the snow piles up quickly there

because it has nowhere to go but up. This is very similar to what can happen in

a hurricane. Sandy is pushing tons of water towards NJ and NY and this water is

essentially trapped in a sharp angle of the coastline.

Hurricane Isaac generated a surprisingly high storm surge in

coastal Louisiana this summer as it pushed water against a similar “corner”

along the Mississippi Delta. Many people were shocked that a category-1

hurricane was able to generate a surge greater than 13 feet high. However, this

large storm kept piling water up against this “corner” in the coastline,

producing a devastating surge in some communities.